Urban design – the part Lissenden Gardens played

It’s not surprising that the development of Lissenden Gardens provoked opposition. The site Armstrong found was in a most exclusive part of Kentish Town: a row of villas, set back behind a green, with Parliament Hill Fields, the southern part of Hampstead Heath behind, and a working farm to the north. Armstrong bought one of villas, which had large grounds, and later bought neighbouring houses that allowed the estate to be extended.

The closely packed four, and later five, storey blocks, described as a ‘monstrous object’ by one protester, must have seemed as out of place in this rural idyll as some of the multi-storey blocks of flats that today are being built in suburban locations.

The gardener’s cottage on the north side of the estate (now demolished) was an unlikely companion for the red brick blocks.

The initial design was for a self-contained, courtyard-like development of four blocks arranged around a garden. Laws had been passed to give local authorities powers to promote public health by controlling house building. These regulations aimed to ensure new homes had adequate light and air and so set out rules about the width of streets and height of buildings. The rules only applied to ‘streets’ so some developers tried to get round the regulations by building private roads or courtyards. Armstrong initially argued that his development was not a street and would have a gate and a porter to stop the public coming in. This idea was defeated in court and Armstrong eventually bought land to the south of the site which enabled him to link the gardens through to Gordon House Road so it met the objections.

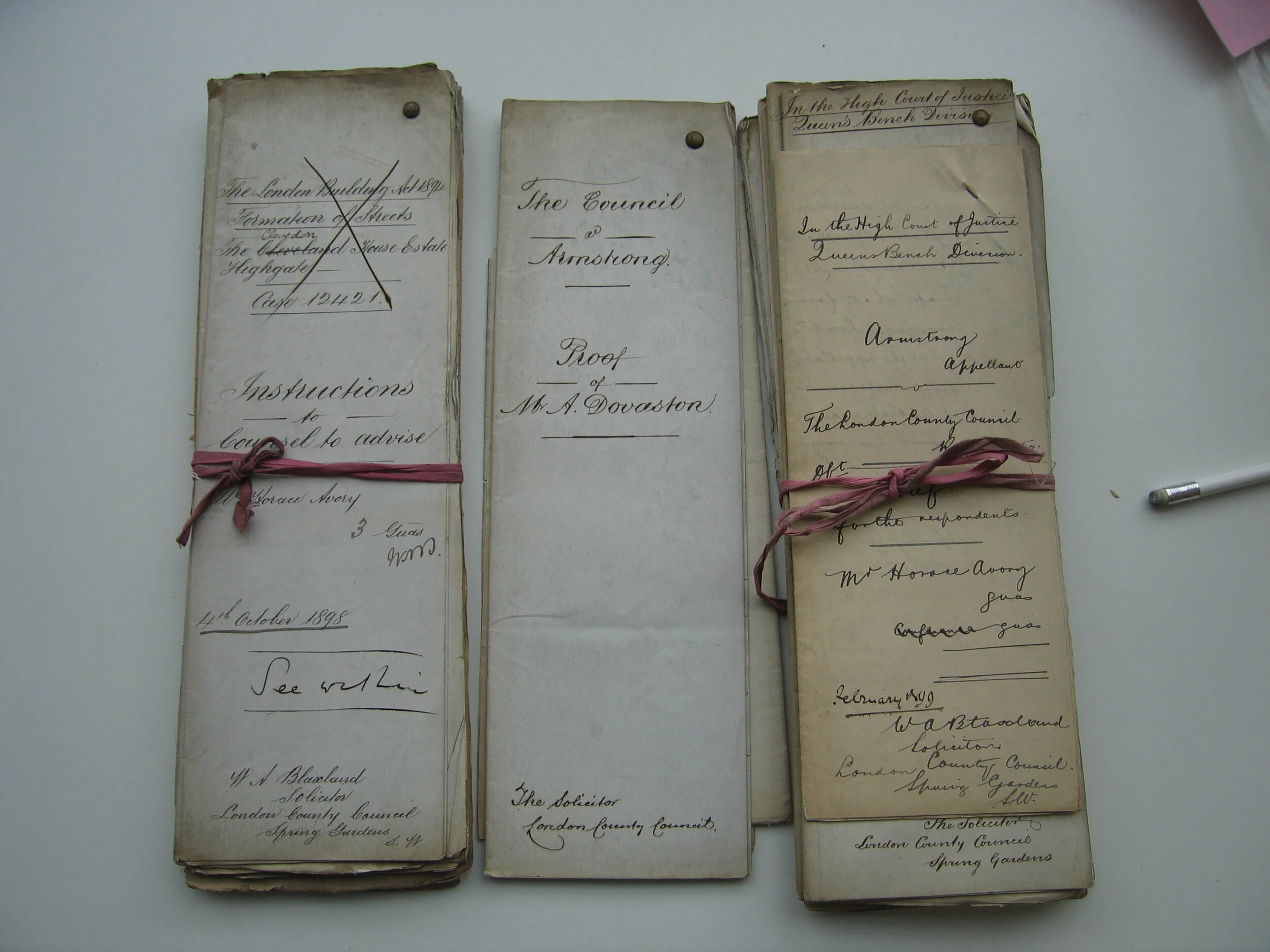

Barristers’ papers from the case the LCC brought against Armstrong also at the LMA

How the site of Lissenden Gardens looked in the early 19th century. Parliament Hill School replaced the big house next to the farm. Detail from The Kentish Town Panorama by James Frederick King

But, as the postcard images show, the estate was carefully designed with ornamental ironwork, a central garden and young plane trees, which now fill the streets with green in summer.

The main architects of the estate were Boehmer and Gibbs, who designed many of EJ Cave’s blocks. The firm presumably benefited from Edward Boehmer’s experience while training as an architect in Germany where comfortable middle-class flats were well established.

Like Boehmer and Gibbs’ other flats, Lissenden Gardens is built of red brick with red render and white ornamentation. All the flats have balconies. The blocks, according to local architect Tony Edwards, are designed in the Arts and Crafts style. The coloured tiles, different in every stairway, are very characteristic of the period.

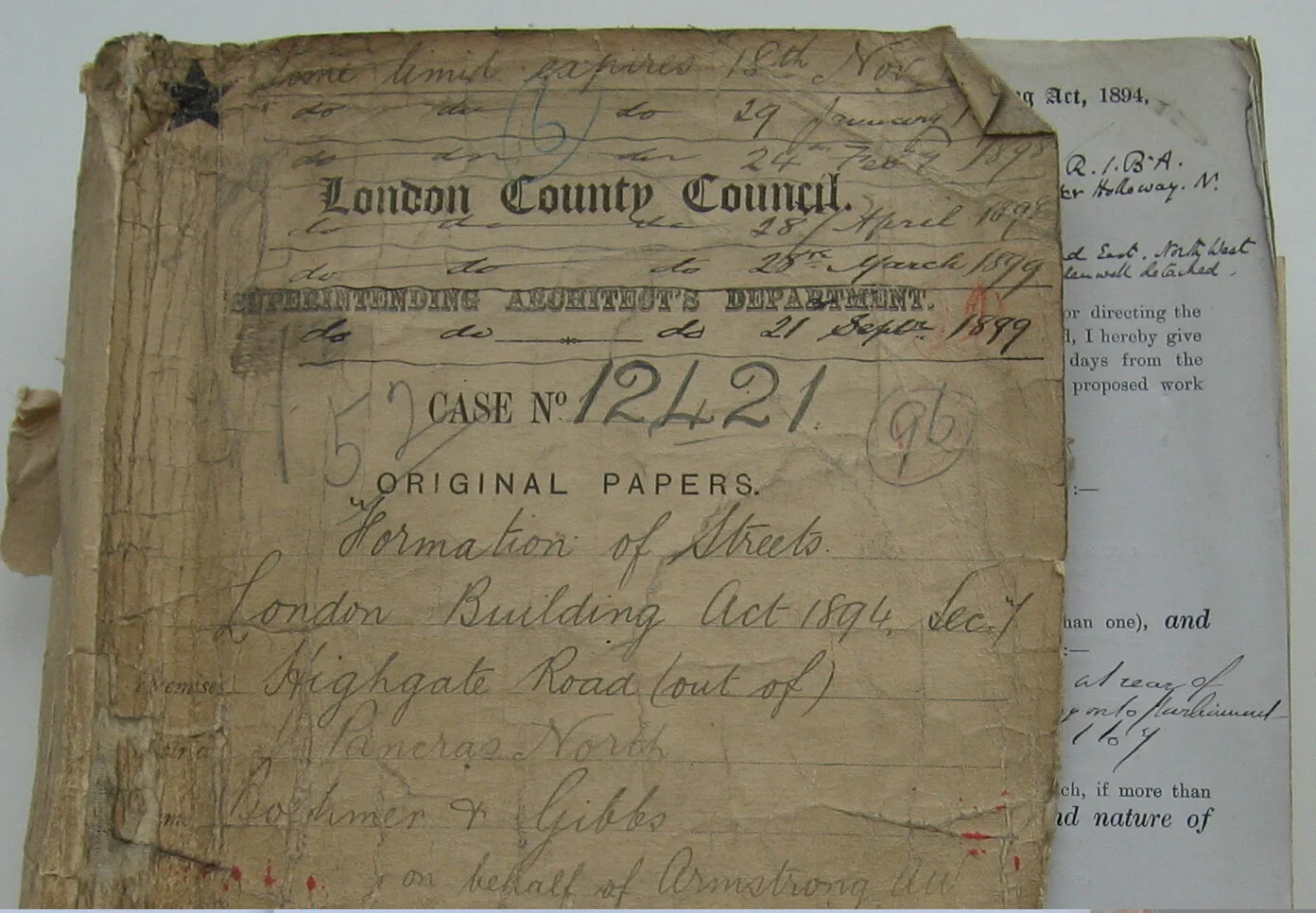

The London County Council file on Lissenden Gardens at the London Metropolitan Archives

Chester Court and 11-20 Parliament Hill Mansions how architectural styles changed Photo: Josh Pulman

To Paradise by Way of Gospel Oak: a mansion flat estate and the forces that shaped it by Rosalind Bayley, is published by Camden History Society and is on sale at The Owl Bookshop or from the author and available at Swiss Cottage Library and the British Library.